Quantum Mechanics Notes/Overview

Information on this page was taken from the Fall 2025 Macalester College Quantum Mechanics course taught by Professor Saki Khan using Griffith’s 2nd Edition.

History of QM

The Wave Function

Physicists needed a mathematical tool to describe particles/waves. This function has to meet a some physics criteria:

- Complex function

- Square-integrable

- Normalizing doesn’t depend on time (the particle has to be somewhere)

Schrodinger Equation

Since all particles can be described as waves (thanks DeBroglie), and a bunch of other criteria, we get the following differential equation in QM, solutions to which are called wave functions:

\[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{\partial^2\Psi}{\partial x^2} + V\Psi = i\hbar\frac{\partial\Psi}{\partial t}\]

Solutions to the Schrodinger Equation are called square-integrable

Statistical Interpretation

What does a wave function actually mean? Max Born provides the interpretation. Specifically

\[\int_a^b|\Psi(x, t)|^2dx = \left\{\text{probability of finding the particle between $a$ and $b$ at time $t$}\right\}\]

Ok. What if I make a measurement of a particle at time \(t\), say at position \(C\)? Where was the particle just before I made the measurement?

Turn’s out there’s three plausible answers.

- (Realist) The particle was at \(C\).

- (Orthodox) The particle wasn’t really anywhere.

- (Agnostic) No answer.

Most physicist take the orthodox view after John Bell’s showed that it makes an observable difference whether the particle had a precise (though unknown) position prior to measurement.

Ok. What if I make a measurement right after the first measurement?

Answer: The wave function collapses and all subsequent measurements yield \(C\).

Probability

In statistics, it’s called the average. In QM, it’s called the expectation value, that is to say the value you would get after repeated measurements.

Normalization

Given our statistical interpretation of the wave function, we will need to normalize the function. We can do so with the following physical condition: at any given time, the particle must be somewhere.

\[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}|\Psi(x, t)|^2 dx = 1\]

Note, once a wave function is normalized at some \(t\), it remains normalized for all other \(t\).

Momentum

Here is a neat fact:

- All observables (eg. energy, temperature, etc.) \(Q\) are functions of \(x\) and \(p\). In other words, \(Q=Q(x, p)\).

Any observable has a corresponding expectation value in QM defined as: \[\left<Q(x, p)\right>\int\Psi^*\left[Q(x, -i\hbar\partial/\partial x)\right]\Psi dx\]

Additionally, we can define operators, essentially functions, that allow us to only have to remember classical equations and two specific operators.

\[\hat{x} = x, \quad \hat{p} = -i\hbar\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\]

Another neat fact is Ehrenfest’s theorem: expectation values obey classical laws, allowing us to translate angle brackets in QM equations.

Uncertainty Principle

We should all know this by now.

\[\sigma_x\sigma_p \geq\frac{\hbar}{2}\]

Time-Independent Schrodinger Equation

Stationary States

When we try to solve the Schrodinger Equation (SE), we use the physicist’s favorite tool, separation of variables, to derive the time-independent Schrodinger Equation (TISE).

\[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2 \Psi}{dx^2} + V\Psi = E\Psi\]

This is especially cool because any time-independent solution we find with this equation can be turned into a time-dependent solution by adding on

\[e^{-iEt\hbar}\]

The key thing about solutions to the TISE are:

- They are stationary states: the probability density (\(|\Psi(x,t)|^2\)) doesn’t depend on \(t\)

- The are states of definite total energy. Note total energy is called the Hamiltonian

- The general solution is a linear combination of separable variables. Specifically, \[\Psi(x,t) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_n\psi_n e^{-i E_n t/\hbar} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}c_n\Psi_n\]

Importantly, \(|c_n|^2\) is the probability that a measurement of the energy would return the value \(E_n\).

Additionally, \[\sum_{n=1}^\infty|c_n|^2 =1\] and \[\left<H\right> = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}|c_n|^2 E_n\].

Infinite Square Well

Given

\[V(x) = \cases{0, \quad 0\leq x\leq a \\ \infty, \quad \text{otherwise}}\]

solutions to the TISE after solving for both regions and applying boundary conditions gives

\[E_n = \frac{n^2\pi^2\hbar^2}{2ma^2}\]

and \[\psi_n(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{a}}\sin\left(\frac{n\pi}{a}x\right)\]

which have interesting properties. Namely

- \(\psi_n\) alternate being even or odd

- \(\psi_1\) has no nodes, \(\psi_2\) has one, \(\psi_3\) has 2, etc.

- They are orthogonal

- They are complete (any other function can be expressed as a linear combination of them)

The third point bring up the key realization (Kronecker delta):

\[\int\psi_m^*\psi_n dx = \delta_{mn} = \cases{0, \quad m\not= n \\ 1, \quad m = n}\]

From part 4 comes the relation

\[c_n = \int\psi_n^*f(x) dx\]

or what is often more helpful (at least in HW)

\[c_n = \sqrt{\frac{2}{a}}\int_0^\infty\sin\left(\frac{n\pi}{a}x\right)\Psi(x,0) dx\]

Harmonic Oscillator

Another cool fact: harmonic oscillators are cool and useful and we can approximate any function as a Taylor series expansion.

Assuming the potential takes the form \[V(x) = \frac{1}{2}m\omega^2x^2\] our TISE becomes \[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} + \frac{1}{2}m\omega^2x^2 = E\psi\]

There are two methods for which to solve this differential equation.

Algebraic Method

With

\[\hat{a}_\pm = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\hbar m\omega}}(\mp i\hat{p} + m\omega x)\]

\[\left[x, \hat{p}\right] = i\hbar\]

It follows if \(\psi\) satisfies the SE with energy \(E\) (that is \(\hat{H}\psi = E\psi\)), then \(\hat{a}_+\psi\) satisfies the SE with energy \((E + \hbar\omega)\): \(\hat{H}(\hat{a}_+\psi) = (E+\hbar\omega)(\hat{a}_+\psi)\)

We call \(\hat{a}_\pm\) ladder operators.

This is particlarly useful because we can find

\[\psi_0 = \left(\frac{m\omega}{\pi\hbar}\right)^{1/4}e^{-\frac{m\omega}{2\hbar}x^2}\]

\[\psi_n = A_n(\hat{a}_+)^n\psi_0, \text{ with } E_n = \left(n + \frac{1}{2}\right)\hbar\omega\]

Additionally, it’s useful to know

\[\hat{a}_+\psi_n = \sqrt{n + 1}\psi_{n+1}, \quad \hat{a}_-\psi_n = \sqrt{n}\psi_{n-1}\]

and

\[\psi_n = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n!}}(\hat{a}_+)^n\psi_0\]

Arguably even more useful: \[x = \sqrt{\frac{\hbar}{2m\omega}}\left(\hat{a}_+ + \hat{a}_-\right), \quad \hat{p} = i\sqrt{\frac{\hbar m \omega}{2}}(\hat{a}_+ - \hat{a}_-)\]

Analytic Method

If we use the analytic method, we get the solution

\[\psi_n = \left(\frac{m\omega}{\pi\hbar}\right)^{1/4}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^nn!}}H_n(\xi)e^{-\xi^2/2}\]

which use the Hermite polynomials!

Free Particle

Our TISE is

\[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} = E\psi\]

or \[\frac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} = -k^2\psi, \quad k = \frac{\sqrt{2mE}}{\hbar}\]

which has a general solution of

\[\psi = Ae^{ikx} + Be^{-ikx}\]

or the time-dependent solution of

\[\Psi_k(x,t) = Ae^{i\left(kx - \frac{\hbar k^2}{2m}t\right)}, \quad k = \pm\frac{\sqrt{2mE}}{\hbar}\]

with \(k>0\implies \text{traveling to right}\) and \(k<0\implies \text{traveling to left}\)

The big thing of free particles is: there is no such thing as a free particle with deifinite energy

Instead we can get a solution using a Fourier transformation to get the wave packet. This wave packet solution helps us see that the quantum and classical velocity of the particle are identical if we define the quantum velocity as the group velocity, not the phase velocity. $$$$

Delta-Function Potential

Bound/Scattering States: Tunneling

If \(E< V(-\infty)\) and \(V(\infty)\), then the system is in a bound state.

If \(E< V(-\infty)\) or \(V(\infty)\), then the system is in a scattering state.

This is a result of tunneling.

Delta-Function Well

Given

\[\delta(x) = \cases{0, \quad x\not=0 \\ \infty, \quad x = 0}\quad \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\delta(x) dx = 1\]

We can consider potentials of the form

\[V(x) = -\alpha\delta(x)\]

We can solve similarly to prior problems, but note that our general solution might take the form

\[\psi = Ae^{lx} + Be^{-lx}\].

For bound states (note, dirac delta potentials result in only one bound state), the solution is

\[\psi = \frac{\sqrt{m\alpha}}{\hbar}e^{-m\alpha|x|/\hbar^2}, \quad E = -\frac{m\alpha^2}{2\hbar^2}\]

For scattered states, the solution is a series of tranmitted and reflected waves.

\[R = \frac{|B|^2}{|A|^2}, \quad T = \frac{|F|^2}{|A|^2}, \quad R + T = 1\]

In our case (a negative dirac delta well),

\[R = \frac{1}{1 + (2\hbar^2E/m\alpha^2)}, T = \frac{1}{1 + (m\alpha^2/2\hbar^2E)}\]

The key takeaways when solving these boundary condition problems are

- \(\psi\) is always continuous

- \(d\psi/dx\) is continuous except at points of infinite potential

Finite Square Well

For a finite square well, with potential

\[V(x) = \cases{-V_0, \quad -a \leq x \leq a \\ 0, \quad |x| > a}\]

We get a transcendental equation (cannot be solved algebraically)

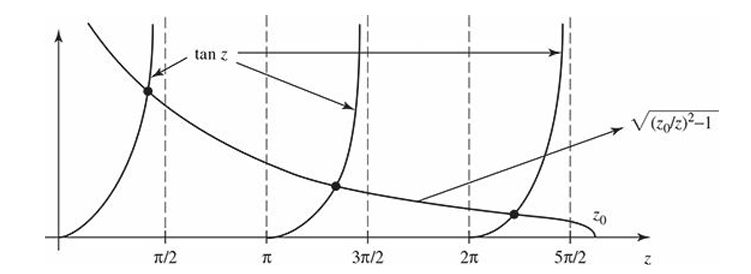

\[\tan z = \sqrt{(z_0/z)^2-1}\]

The graph of which looks like

What is interesting about this solution is

- For a wide, deep well, the well looks like an infinite square well

- For a shallow, narrow well, there are fewer and fewer bound states, but one state is always present.